Step One: It Is Easy Being Green

You don’t have to be any kind of energy expert to understand that to reduce your climate footprint, you should try to use energy from sources that don’t emit greenhouse gases, especially renewable resources like solar and wind – what many refer to as “decarbonizing” or “greening” your energy supply.

The good news is that as clean energy technologies have become significantly cheaper over the last few decades, the market has flourished with plenty of climate-friendly options out there. In this step, we’ll go over how to tap into that market with a minimum of effort and maximum results. Kermit the Frog may still find it’s tough “bein’ green,” but that’s less and less true for those of us looking to use clean energy at home. (Note that I’m focusing here on switching to clean supplies for electricity and, potentially, natural gas. If you’re dealing with home heating using propane or oil, we’ll get to that in Step Two.) And once you’ve switched over to clean energy, you can ratchet down the thermostat on a hot summer day, lie back and relax, and stop worrying you’re making the climate problem worse.

The Basics

The main difficulties you may face are (1) in accessing this growing clean energy market if you get your energy from a monopoly utility, which can limit your choices to whatever that utility might offer; and (2) in making smart choices as to what you spend your money on as a clean energy consumer.

Before we dive in, let’s quickly review four main categories of energy resources, each with their own characteristics, that you may be running into in your search for green energy: renewables (solar, wind, hydropower, and geothermal, all of which tap into “fuel” sources that generally aren’t limited in supply); carbon-free energy (renewables plus nuclear); renewable natural gas or biogas (which can be used at your home or to generate electricity at a power plant); and fossil fuels. Fossil fuels, which you may hear called “brown” energy, include coal, natural gas, oil, and propane. Natural gas does in fact produce less greenhouse gas (in the form of carbon dioxide) when you burn it than a fuel like coal, but one of the most powerful greenhouse gases – methane – can leak in large quantities during the gas extraction and transportation process. Overall, there’s no debate that producing and burning natural gas does result in a significant amount of greenhouse gas emissions, which is why I lump it in with coal and oil.

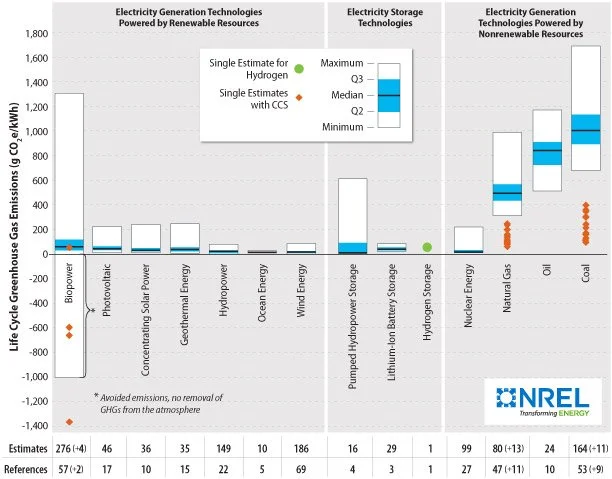

Experts have written volumes about the climate and environmental pros and cons of each of these energy resources, which I won’t rehash here. Instead, let me be upfront that I’m relying on expert analyses showing that for purposes of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it makes sense to shift our energy use as much as possible to carbon-free energy, i.e., renewables and nuclear. For example, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy) has synthesized a broad range of data regarding life-cycle emissions of various energy technologies, including from raw materials and construction, to show that on average carbon-free technologies offer a significant improvement over natural gas, oil, and coal:

NREL Life Cycle Assessment Harmonization, https://www.nrel.gov/analysis/life-cycle-assessment.html.

You may realize already that the easiest way to switch to carbon-free energy is to use electricity generated from renewable or nuclear sources — which is why Step Two focuses on shifting more of your home energy use to electricity. But before that you’ll want to make sure that the electricity you’re using is in fact coming from carbon-free sources. That’s getting easier and easier as costs of renewables come down and clean energy markets mature, but the pointers below also cover how to make sure you’re getting good value for your money. After all, the less you spend on Step One, the more of your climate budget you can save for the other steps along the way.

What about natural gas, you ask? There’s certainly lots of time and energy going into developing “renewable” natural gas, or biogas, which is natural gas produced from organic sources rather than the traditional approach of extracting it from the ground. Since natural gas is mainly composed of methane — a far more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide — scientists have developed processes to capture natural gas supplies from waste methane sources such as emissions from wastewater treatment plants and landfills, or organic waste (yes, poop) from dairies and livestock farms. Ostensibly, this means renewable natural gas can be used for energy with a lower net climate impact because it diverts waste methane emissions that would otherwise end up in the atmosphere anyway.

A few “buts” are in order here. First, burning any form of natural gas, whether for home heating or cooking, does still result in carbon dioxide emissions, and there is significant debate about the overall climate impact of different biogas production processes. Even putting those issues aside, for the moment carbon-free electricity seems to be more accessible and cost-effective than renewable natural gas over the next decade or more (at least in the United States). A recent study of potential supplies of renewable natural gas — commissioned by a gas trade group — found that they could satisfy only a small percentage of total U.S. natural gas consumption. In addition to being less plentiful than clean electricity, in many places renewable natural gas is also more expensive. (If you do run across a surprisingly cheap option, it may be traditional natural gas paired with “carbon offsets” from independent sources, which is sometimes marketed as “clean” or “green” natural gas; the Next Steps section offers more discussion of that approach.) That’s why the information below focuses on moving to carbon-free electricity as the best long-term option. Still, to the extent you’re sticking with natural gas, at least in the near-term, most of the below is still applicable; just look for information on “renewable natural gas” or “biogas.”

The When

When can you most easily make the switch to clean energy? Conveniently – unless you’ll be installing solar or some other form of power supply actually located at your home – changing to clean energy won’t involve any major projects or up-front costs that would affect potential timing. You’ll still be getting electricity or natural gas through the same wires or pipes. It’s just that when you pay your utility bills, that money will go to a source behind those wires and pipes that’s cleaner than before. That means your decisions here will depend mainly on the availability and quality of affordable products, whether through your monopoly utility or a third-party energy supplier, rather than any logistical considerations about home improvements.

The product and pricing options for clean energy can be driven by a range of factors, whether it’s technological innovation, federal tax incentives, utility procurement choices, or local and state energy policy. Because all of these factors are subject to change over time, it makes sense to periodically look over the choices at hand and figure out if you’re on the right track. Some options for when to tackle that “clean energy check-up”:

When you move, right alongside your Step Zero planning.

If you get energy through a contract with a limited term (often a year or two), a month or two before that contract expires.

When you’re tackling some of the other issues covered in this book and have energy on the brain already.

Annually on Earth Day (reminder: that’s April 22).

Really, any time is a good time — but as my husband would say, you just need to figure out a system that works for you and stick to it. (Don’t tell him my system for getting the car washed is to wait until he complains about how grimy it is. It works for me!)

Home Solar

There are some specific timing considerations to keep in mind if home solar is on your list of potential energy options. (I’m assuming solar is the most viable option for most folks, given the current costs of geothermal systems.) These generally relate to making sure that you take that step when it fits the best with your living situation and when you can get the best value for your investment:

When you’re moving to a home where you plan to stay for long enough for the system to pay back its cost and start saving you money – currently on average about 8 or 9 years in the United States, although that may vary a lot depending on where you live.

If available financial or tax incentives are scheduled to decrease or run out; in the United States, the biggest ticket item is generally the federal tax credit. You can find up-to-date information on this (and other issues related to home solar) on the EnergySage website, or home solar contractors will likely bring relevant deadlines to your attention if you reach out to get installation quotes.

If there’s an opportunity to reduce the cost of purchasing solar panels by participating in a local solar “co-op” or “solarize” program where residents band together to purchase systems from a single company in order to get a bulk discount. (More information here.)

For a rooftop system, when you’re replacing your roof or within a few years of doing so. Solar panels can last 20 or 30 years or more, so matching up that timing can ideally help avoid the need for another roof replacement until the panels themselves have reached the end of their lifetime. This is not a dealbreaker; if you don’t get perfect overlap you’ll just want to make sure you’re aware of potential costs of labor to remove and reinstall the solar panels at your next roof replacement.

So, should you be thinking about home solar? It is definitely a bit more complicated than just changing what type of energy you purchase. If reading through the items above made your palms sweaty and you want to table the topic for now, that’s fine. If you’re excited at the prospect of investing in your own on-site system that could end up saving you money over fossil fuels in the long term, that’s great too. Remember: the point here is to make smart choices that are right for you, not to feel like you have to become a clean energy expert and figure out the perfect option.

The How

Where to Look

The first question for you to answer at this point is pretty simple: where can you get carbon-free energy from? Generally, there are four main options to consider:

Your monopoly utility: This is the “wires” or “pipes” company that makes sure energy gets to your home from wherever it might be produced. You can check their website or call their customer service line to find out whether they offer any carbon-free energy choices, sometimes called a “green tariff.” You may also see references to “community solar” or “solar gardens” depending on the type of program, more on that below.

Third party energy suppliers: This option applies if you live somewhere that permits you to shop for energy in the private market. There are some websites that let you review offers from multiple suppliers at once, or you can go to an individual company’s website to see what they offer for green or renewable energy. As with a monopoly utility, you may see community solar or solar garden subscriptions as an option. Overall, this avenue is probably the closest you can get in the energy world to a normal consumer experience like grocery shopping, where there are a range of choices and it’s up to you to evaluate the price and quality of a company’s offers. Although there is usually some government oversight aimed at preventing outright consumer fraud by these energy suppliers, as with many business sectors there are good and bad apples, and often it’s up to you to vet what you’re buying — good old caveat emptor.

Community energy supply: In some places, you can choose to get energy through community procurement by your local government. Sometimes this requires enrollment in a particular time period, but usually there’s more than one bite at the apple if you miss your chance and want to try again down the line. A community “aggregation,” as this approach is sometimes called, may offer clean energy options, a range of “green” and “brown” alternatives, or just the standard energy supply at a bulk discount.

Self-generation: Subject to whatever screening is required by your utility in what’s called the “interconnection” process, you can explore installing your own electric generation at home. This might also include a battery storage option. Note that home solar generally does not provide backup power during an outage, unless you’re specifically setting it up that way with your contractor and utility. If that’s what you’re looking for, you may also want to read Step Two for more information on the potential for getting back-up power from an electric vehicle.

Having trouble figuring out exactly what’s on the table for your energy supply? I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: you don’t need to become an energy expert, you just need to know how to find them. In many cases, you can call the agency that regulates your utility (information for each U.S. state is available here) or look on their website for information about consumer choice and green energy options. There may also be a separate organization (either a government agency or non-profit) in your state with the specific mission of advocating for residential utility customers, and often they can provide information about switching energy supply — if they’re on the member list for the National Association of State Utility Consumer Advocates that’s a good sign. Even your utility will be able to give you some basic understanding of what your choices are, although it’s generally not their job to give customer-specific advice.

What to Look For

Is It Actually Carbon-Free?

A lot of people equate the term “green energy” with wind, solar, and maybe hydropower or geothermal. But it could include nuclear or biomass as well. I’ve even seen references to green power that encompass “clean coal” or efficient natural gas plants. Many of the terms used in marketing clean energy are not precisely defined or are defined differently depending on where you live and what regulations apply. That’s why it’s important to take a look behind the curtain of a “green” label to see if what you’re buying matches up with what you actually want to achieve, with respect to climate impacts or otherwise. Knowing exactly what the product is will also help you figure out its value to you when you get to the price comparison stage below.

So how do you answer the question of what type of green energy you’re really looking at? This is where you probably need to look past the marketing claims. Fortunately, most states require energy suppliers to provide some type of detailed environmental disclosure for their consumer offerings. Look for that (it may be buried on a website or you may need to affirmatively ask for it), and you should find some explanation of whether the “green” energy comes from wind, solar, biomass, geothermal, nuclear, hydropower, or some mix. It is still generally illegal to lie outright to consumers, so if a given product is explicitly labeled as “solar” or “wind and solar” then checking the environmental disclosure may fall in the category of a belt-and-suspenders approach. But one way or another, figuring out the actual type of energy resource behind a green energy offer is an important step to make sure you’re making a smart choice.

Where Is It From?

This question probably doesn’t make any sense unless you know that a green energy label has nothing to do with the actual purchase of energy. If you’re buying something labeled “renewable” energy, you’re actually buying a “renewable energy certificate” (also called a “renewable energy credit”), or REC. That’s an entirely made-up concept based on the abstract idea that one unit of energy generation (a megawatt-hour) from a renewable energy source equals one REC representing the environmental attributes of that energy generation. The same concept applies to generation from something like a nuclear plant, even if it doesn’t qualify explicitly under an applicable definition of “renewable” energy; the plant owner is free to sell the carbon-free attribute of the nuclear generation as a separate product from the actual electricity from the plant, as long as someone is willing to buy it.

It may seem like a strange concept to wrap your head around, but think about it like money: if you give someone a dollar for a candy bar, that’s based on an agreement that the right piece of paper issued by the U.S. Treasury represents a value that the other person recognizes and is willing to accept. In this case, the REC or other green product is like that dollar bill, except instead of representing a monetary value it represents an agreed-upon environmental value. Whoever produced that environmental good from a given energy generation facility can turn around and sell the actual energy from that facility to someone else entirely, as long as that other person doesn’t also claim they’re getting green energy too. The green “attribute” has been sold to you.

The answer to the question of where the green component of your electricity supply is coming from matters for one main reason. If the source of the REC or other environmental attribute isn’t on the same electric “grid” as you, you may not actually be directly displacing fossil fuels where you live. You can buy enough RECs to offset every kilowatt-hour of your electricity use, but if those RECs don’t come from a source on the same grid as you, you’re still paying for electrons from whatever generation is on that grid. Depending on where you live, that may well be mostly coal and natural gas resources. In fact, it may be that a green energy product is less expensive exactly because it’s coming from somewhere that has a surplus of clean energy that’s being sold off at low cost, while your actual electrons are coming from cheap “brown” resources nearby.

Yes, buying RECs or any similar green energy product is going to generally help support clean energy development by increasing demand for and therefore the value of clean energy resources. But we’ll never phase out fossil fuels until we stop getting our actual electricity from coal and natural gas-fired plants. (This is assuming it remains infeasible to capture and store the carbon dioxide emissions from those plants, as seems likely to be the case for years if not decades to come.) Now that you know that buying “green” may mean your electricity supply itself is still coming from fossil fuels, hopefully it makes sense that you should also consider whether your green power is actually located on your electric grid and can play a real role in shifting the overall energy mix to carbon-free resources.

How do you know whether that’s the case? This is not an exact science - unless you’re an electrical engineer and want to do a power-flow study to model where your electricity is coming from. I assume not. There’s also not an easy standard reference point like the environmental disclosure statement discussed above. But you can at least read the marketing claims and background materials for a given offer. Many utilities and suppliers understand the appeal of “community” energy, and try to make it a selling point. Even clean energy from your “region” is likely to be a good option, since it’s fairly common to be part of a regional electric grid where energy flows across traditional political boundaries. These geographic keywords — “local,” “community,” “state,” “regional” — can help you identify whether a green energy purchase is not just supporting clean energy in general, but in fact helping to transition your actual energy supply to be more climate-friendly.

How Is It Different?

Just two more things to consider as you’re pondering a switch to carbon-free energy. First, you should know what you’re switching off of – that is, how clean is your background electricity supply? Most places are still well below 100% renewable energy, and even well below 50%. For the U.S., the federal Energy Information Administration tracks actual annual state consumption of different types of energy, and as one example my own state of Ohio got less than 3% of its electricity from renewables and just 16.4% from nuclear power in 2019. (If you want to get a reasonable idea of how much shifting to 100% carbon-free energy can reduce your climate footprint, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has a calculator that provides zip code-level figures for baseline greenhouse gas emissions based on your monthly electricity usage versus a 100% renewable supply.)

Second, with more ambitious clean energy policies being instituted worldwide, it’s worth knowing if your utility or community is already planning to shift its supply to 50% renewables over the next several years, or if your state or territory is instituting a carbon cap on electricity generation to bring greenhouse gas emissions down significantly over the next decade. That doesn’t mean your purchase of clean energy wouldn’t be helpful to accelerate or complement those changes. But, as you’ll see in the following steps, there are other investments you can make that are essential to making your clean energy transition. If your climate budget doesn’t leave room for switching to green electricity and buying an electric vehicle at the same time, think about which choice is harder to revisit; probably the latter. As crazy as it may seem – and even though this is called “Step One” – if you can’t afford to decarbonize, electrify, and automate all in one fell swoop then I’d recommend you focus on the most irrevocable choices first to get those right. Switching to carbon-free energy may not be at the top of that list.

Finally, there’s that lingering question about home solar, or solar plus battery storage if that’s on your menu. Weighing this against buying carbon-free energy off the grid can be complicated. It may cost more or less — a solar contractor can give you a quote for installation costs and estimate of whether it’s an investment that will save you money compared to other options. It may also be the easiest way to access carbon-free energy if you live in a place where you can’t “shop” beyond your monopoly utility and that utility doesn’t have any good offers (although that’s becoming more rare). Home solar can also be less flexible than enrolling in a carbon-free offer on a monthly or yearly basis. Of course, you’ll also want to take into account the many other less tangible factors like how excited you’ll be to see those panels on your roof and talk to your neighbors about the project. As a solar owner myself, I’m well aware that investing in your own home to improve your climate footprint has its attractions. And if there is a battery back-up option that you can afford, and you live in a place where power outages are a real problem, the ability to get back-up power may be a compelling consideration. (If you’ve heard of a public safety power shutoff you know what I mean.) Ultimately, this one is a personal decision that depends on which issues – price, flexibility, reliability, or others – are most important to you.

Looking Ahead

One more consideration on this front: make sure you review Step Three before you go ahead and sign up for a green energy option. That will be important for you to understand your choices if you’re running into options that involve “time-of-use” or “off-peak” rates, or “demand response” programs. I’m flagging that now to help avoid confusion, but we’ll get into the details later — one step at a time, as they say.

How Much to Pay

Once you’ve figured out what the options are versus what you’re looking for, whether it’s Renewable Energy Certificates from anywhere in the country or solar from your community, the key question will be what fits in your climate budget. To figure that out, you’ll want to know how much you’ll pay for what you want, and I’m going to walk you through that step-by-step. This bit is long, but by the end you’ll hopefully find the carbon-free energy supply you want, so bear with me.

Generally you’ll see prices for electricity in cents per kwh (kilowatt-hour). There may be a wide range, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the high prices are too high or the low prices are a scam; as discussed above, there can be real differences in product quality behind these different charges. Of course, it’s impossible to evaluate these numbers in a vacuum. Next you’ll need to figure out a baseline for comparison. I’d recommend you look at the utility’s default or “provider of last resort” energy price for customers who haven’t chosen any alternative, since that’s either what you’re paying now or what you’d pay if you were entering the market for the first time. You may have already come across that price in the resources you’ve found so far, but if not you can generally get the information from your utility, your utility regulator, or a consumer advocacy organization, either by phone or on the Internet. If you’re really lucky, your utility may have some type of rate comparison tool, although sadly those are relatively rare. (See the Politics and Prejudice section for more on what you can do about addressing problems like that.)

You may be wondering why I don’t just tell you to look at your utility bill? Feel free! But utility bills can get confusing because they don’t always separate out how much you’re paying for your actual energy supply versus the “distribution” or “transportation” costs for getting the energy to your home, or they may have several different charges that you need to add together to figure out the total relevant energy charges. If you are going to try starting with your bill, you should look for key terms like “generation” or “supply” charges, or even better if the bill identifies a “price to compare” to use in shopping for energy.

One slight twist you should look out for: the timeframe. Sometimes energy prices can vary by season, month, or even time of day (often called a “time-of-use rate,” we’ll delve more into that in Step Three). The important thing here is to ensure you’re making an apples-to-apples comparison to see how much of a price premium you’d pay for the clean energy component of the default energy supply. The same goes if you live in one of the handful of places, most notably Texas, where there’s no default service offer and you get placed with a third party energy supplier no matter what. If that applies to you, your best bet is similarly to look for the comparable prices for normal “brown” power under the relevant contract term or time-of-use rate structure.

Once you’ve figured out a baseline price for “brown” energy, and some clean energy options to compare it to, you can start getting a sense of the cost differential between the standard energy supply and your clean energy options. It’s not impossible that there may not be much of a difference at all, especially for generic “green” electricity options – as discussed above, that may be because you’re buying cheap RECs from somewhere across the country where there’s already plenty of renewable resources. But sometimes you’ll see differences of several cents per kilowatt-hour. You may also find clean energy supply offered at a fixed dollar cost per month rather than a higher charge per unit of energy, in which case you can just multiply that by 12 to figure out the annual cost and skip the next couple paragraphs.

Assuming you are dealing with a price premium per unit for a range of clean energy options, you’ll probably want to know what that means for your actual monthly bills. (If price is no obstacle, then again, you can skip this part and just sign up for whichever option best meets your clean energy goals.) Here comes the hardest part – but not too hard, I promise: the best approach is to get a year’s worth of utility bills for your home and add up twelve months of usage to figure out how much electricity you consume annually. Most utilities have some way for you to download your monthly energy usage and bills in a spreadsheet format, which can make this step fairly easy depending how painful your utility’s website is to use. If it’s too painful, the utility call center may be able to provide the relevant figures by phone.

If you’re really not a fan of spreadsheets or customer service representatives, you can just use one month; either a high-use month (usually summer for electricity) to get a top-of-the-range figure, or what you’d consider a “typical” month for a rough average cost estimate. Or if you haven’t lived in your home for a full year, you may have to be satisfied with a partial view based on however many months you have been there. Last but not least, some common sense will have to apply here – if you lived through the Texas energy crisis in February 2021 you probably don’t want your “typical” year to include that once-in-a-lifetime event. No matter what approach you take, since none of us can predict the weather or our home energy usage years in advance, just do your best and know that this is not an exact science.

Next comes the simple math: multiply the price premium for your clean energy supply option by your usage for the relevant timeframe. That should get you a dollar per year (or month) estimate you’d be paying extra for clean energy if you sign up for whatever offer you’re looking at. Here’s an example to illustrate the basic concept:

Annual electric usage: 12,000 kilowatt-hours per year

Baseline electricity supply price: 10 cents per kilowatt-hour

Clean energy supply price: 10.5 cents per kilowatt-hour

Per unit price premium: 0.5 cents per kilowatt-hour

Annual price premium: $0.005 per kilowatt-hour x 12,000 kilowatt-hours = $60

Home Solar

If you do think home solar is a viable option (you’re not a renter, you have the ability to install panels on a roof or empty piece of property, etc.), you’ll want to get at least an initial quote or estimate from local installers that can incorporate available incentives and pricing as well as the solar potential of your home. These quotes can also offer an overview of different financing options if you don’t want to or can’t afford the up-front cost of a system, or if there’s any available “lease” model where a third party installs and owns the panels and you just pay for the electricity they generate as part of your monthly utility bills. Overall, if you’re going down this road, the EnergySage website I mentioned above is a good place to start.

It can be hard to do a head-to-head comparison between home solar and purchasing clean energy from the market, especially since home solar may actually pay for itself under the right circumstances — sort of like owning a home instead of renting, with almost as many variables to consider. Still, having cost estimates in hand along with an expert explanation of what bang (or charge) you’ll get for your buck will at least let you consider whether home solar is within your budget and evaluate it on its own terms.

Ideally this is a straightforward enough exercise that you can run through it for several options, but don’t feel like you have to find and evaluate every clean energy offer out there. In particular, if you’re looking at getting clean energy supply from a third-party energy supplier, you may want to do some due diligence ahead of time to find a selection of companies have seem to have a reasonably good reputation – whether through word-of-mouth, the Better Business Bureau, or reviews on customer websites – and focus on offers from those suppliers.

At this point, the final step is simple: look at how much each choice will cost and what you’ll get in return. If you can pay $60 a year and get 100% renewable energy when your annual energy costs are already $1000, that may seem like a pretty good bargain. If you can pay $90 a year instead of $60 and make sure that renewable energy is from a source that’s contributing electricity to your local or regional grid, that extra $30 may be worth it. I can’t make that choice for you, but at least you’re now equipped to make a smart one.

Whatever you do choose, remember – your choices may be very different in a year or two or three. As I recommended in the “when” part of this discussion, you should repeat the “how” piece periodically to make sure you’re continuing to take advantage of decreasing clean energy prices and increasing clean energy options. There may never be a perfect choice out there, it’s true. But once you know what you’re doing, you may be able to get pretty close when it comes to decarbonizing your energy use.